A music video is a variable-length video that combines a music song or album with pictures created for advertising or creative musical objectives. Modern music videos are primarily made and used as a form of music marketing to promote the purchase of music recordings. Music songs are sometimes used in tie-in music marketing efforts, becoming more than just a song. Tying-ins and music merchandising can benefit toys, food, and other things. Dive into the dynamic world of music videos.

Although the origins of music videos may be traced back to the first musical short films, they rose to prominence again when MTV created a framework based on the medium. “Illustrated”, “filmed”, “promo film,” “promo clip,” “promo video,” “song video,” “song clip,” or “film clip” were all the titles used to describe these types of videos.

Music videos contain a variety of styles and modern video-making techniques, such as animation, live-action, documentary, and non-narrative techniques like in the abstract film. Some music videos combine animation and live-action with music in unique ways. Because of the variety of the audience, combining these styles and techniques has become more common. For example, many music videos portray visuals and settings from the song’s lyrics, while others are more theme-based. Other music videos can be merely a filmed rehash of a song’s live concert performance. We have a guide if you plan to create a music video. You can click here to access the album.

History and Development of Music Videos

To showcase the sales of their song “The Little Lost Child,” sheet music publishers Edward B. Marks and Joe Stern recruited electrician George Thomas and several performers in 1894. Using a magic lantern, Thomas projected a sequence of still images on a screen simultaneously as live acts. The illustrated song, the first step toward a music video, would become a popular form of entertainment.

Talkies, Soundies, and Shorts

Many musical short films were made after the debut of “talkies.” Many bands, vocalists, and dancers appeared in Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone shorts. Screen Songs, an episodic series of sing-along short cartoons created by animation artist Max Fleischer, enabled viewers to sing alongside popular songs by “following the bouncing ball,” which is comparable to a modern karaoke machine. Popular singers would perform their hit songs on-camera in live-action sequences during early ‘cartoons.’ Walt Disney’s early animated films, such as the Silly Symphonies cartoons and, in particular, Fantasia, which featured multiple renditions of classical compositions, were created around music. The Warner Bros. cartoons, now known as Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, were created to promote upcoming Warner Bros. musical films. Theaters also received live-action musical shorts starring popular performers such as Cab Calloway.

Video: History of Music Videos.

Bessie Smith, a blues singer, starred in the two-reel short film St. Louis Blues, which featured a dramatized version of the hit song. During this time, several other musicians surfaced in short musical pieces.

Soundies were musical films that typically incorporated short dance sequences akin to contemporary music videos and were produced and released for the Panorama film jukebox.

Louis Jordan, a musician, created short videos for his songs, some of which were stitched together to form Lookout Sister, a feature film. Music historian Donald Clarke states that these films were the “forefathers” of the music video.

Another essential antecedent to a music video was a musical film, and some well-known music videos have emulated the style of classic Hollywood musicals from the 1930s to the 1950s. Madonna’s 1985 music video for “Material Girl”, based on Jack Cole’s presentation of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” from the movie Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is one of the most well-known instances. A number of Michael Jackson’s music videos clearly showcase the strong influence of classic Hollywood musical dance sequences. Two noteworthy examples include the iconic “Thriller” video and Martin Scorsese’s “Bad.” “Bad” drew inspiration from the stylized dance “fights” seen in the film adaptation of “West Side Story.” DJ and singer J. P. “The Big Bopper”

Video: Madonna – Material Girl

According to the Internet Accuracy Project, Richardson was the first to create the term “music video” in 1959.

Tony Bennett states in his memoirs that he created “…the first music video” when he was videotaped walking around the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London, and the resulting clip was placed to his recording of “Stranger in Paradise.” The film was broadcast on programs such as Dick Clark’s American Bandstand in the UK and the United States.

The Czechoslovakian “Dáme si do bytu”, ideated and directed by Ladislav Rychman, appears to be the oldest example of a promotional music video resembling more abstract, current videos.

How Do You Make Your Own Music Video?

To make your own video you should be following three things:

Attending Film School

It is crucial for individuals aspiring to become directors in film, music videos, or other similar mediums. This profession demands specific training and the acquisition of various skill sets. It involves comprehending the visual aesthetics of music videos as well as the integration of music within them. Additionally, numerous essential steps must be taken before stepping onto the set and after completing the shoot. Hence, the importance of enrolling in film school cannot be overstated, as it provides invaluable education and guidance on the art of crafting compelling music videos. Film school provides a comprehensive learning environment to acquire essential skills and techniques for executing a successful shoot. Moreover, certain film schools even offer specialized classes centered around music videos, given their distinct position within the industry.

Working as a Production Assistant

Regardless of your decision to attend film school, nothing can surpass the valuable experience gained from working on real-world sets. In virtually every shoot, there is always a demand for more Production Assistants or PAs. There are two key benefits to this hands-on experience. Firstly, you will gain valuable knowledge and skills in creating music videos. Secondly, you will establish valuable connections with fellow creatives and technicians within the music video industry, which can greatly enhance your prospects of securing future job opportunities.

Get in Touch with Your Musician Friends

Chances are, if you’re interested in establishing yourself in the realm of music videos, you probably have friends who are aspiring musicians as well. So why not collaborate and support each other? Even if you’re still honing your skills as a music video director, it’s never too early to put your knowledge to the test with a friendly client like a close friend. Although you may not receive monetary compensation, the experience you acquire is the true reward. Moreover, by collaborating with your musician friends to produce cost-effective music videos, you will gradually develop the required skill sets and bolster your resume. As a result, you will eventually be able to transition to more prestigious ventures with greater compensation.

What Does a Music Video Director Do?

A music video director is a creative professional responsible for visually bringing a song to life through film or video. Their primary role is translating the artist’s vision and the song’s narrative into compelling visual storytelling. This involves several key responsibilities:

Conceptualization

Directors work closely with artists or record labels to develop a concept or storyline that complements the song’s lyrics and mood. They may create storyboards, shot lists, and mood boards to plan the video’s visual elements.

Filming

Directors oversee the production process, including casting, location scouting, and crew coordination. They direct the actors and musicians, ensuring their performances align with the video’s concept.

Cinematography

Directors work with cinematographers to determine camera angles, lighting, and composition to capture visually stunning and thematically relevant shots.

Editing

Post-production involves editing the footage, adding special effects, and synchronizing the visuals with the music. Directors collaborate with editors to ensure the final product aligns with their vision.

Visual Style

Directors establish the video’s visual style, which can range from realistic to highly stylized, depending on the concept and genre.

Budget Management

They manage the video’s budget, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently to bring the concept to life.

Music Videos During 1960-1973

The Scopitone, a visual jukebox, was launched in France in the late 1950s, and several French artists, including Serge Gainsbourg, Françoise Hardy, Jacques Dutronc, and the Belgian Jacques Brel, produced short films to accompany their songs. The Same kind of machines, such as the Cinebox in Italy and Color-sonic in the United States, were patented as a result of its widespread use. Manny Pittson began pre-recording the music audio for the Canada-produced show Singalong Jubilee in 1961, then went on location and shot various visuals with the musicians lip-synching, then combined the audio and video. Kenneth Anger’s experimental short film Scorpio Rising, released in 1964, substituted popular music for speech.

Alex Murray, the producer of The Moody Blues, wanted to promote his rendition of “Go Now” in 1964. He produced and filmed a short film clip to promote the record, with a striking visual flair that anticipates Queen’s similar “Bohemian Rhapsody” video by a decade. It also predates the Beatles’ promotional films for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” released in 1966.

Video: Go Now (1964) – Music Video

A Hard Day’s Night, which Richard Lester directed, was the Beatles’ debut feature film, released in 1964. It was shot in black-and-white and presented as a faux documentary, with musical tones inserted between comedy and dialogue scenes. The musical segments served as basic blueprints for several following music videos. It directly inspired the popular US TV show The Monkees (1966–1968), featuring film pieces developed to accompany various Monkees songs.

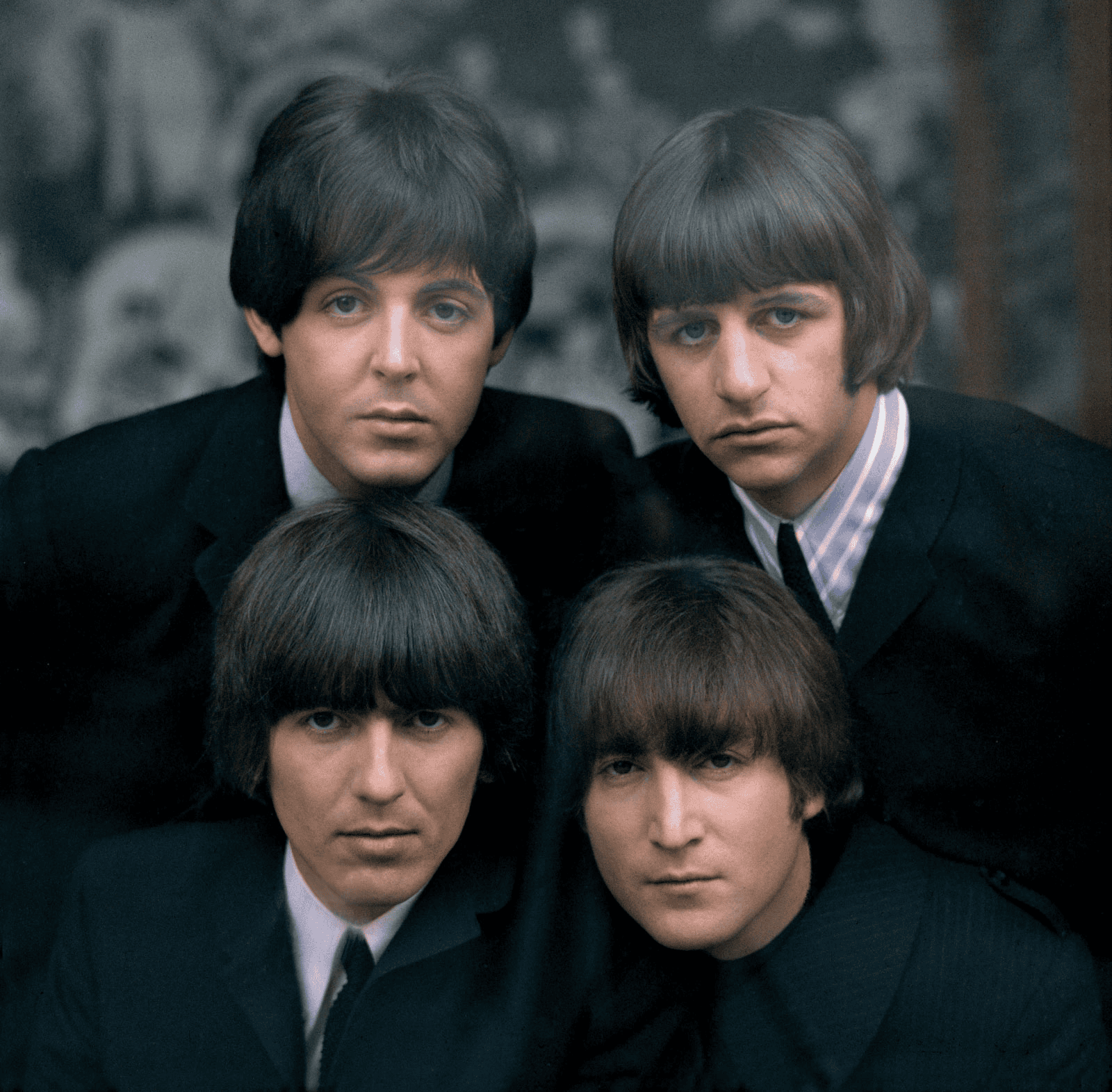

Members of the band, “Beatles”.

The Beatles’ second feature film, “Help!” released in 1965, marked a significant departure from their previous work. It was a more lavish production, filmed in color in various locations in London and worldwide. One of the standout moments in the film is the black-and-white title track sequence, which is often considered a pioneering example of the modern performance-style music video. This sequence incorporates several innovative techniques, including rhythmic cross-cutting, the use of both long shots and close-ups, and unconventional camera angles.

For instance, at approximately the 50-second mark in the song, there is a striking shot that sharply focuses on George Harrison’s left hand and the neck of his guitar. In contrast, John Lennon appears completely out of focus in the background while singing. This particular sequence marked a groundbreaking moment in music video production and has since become an iconic representation of the band’s innovative and experimental spirit.

In 1965, The Beatles initiated the filming of promotional clips, then referred to as “filmed inserts.” These clips were intended for distribution and broadcast in various countries, particularly the United States. They served as a means to promote their record releases without the necessity of making personal appearances. Their initial promotional films, which were shot in late 1965 and featured their then-current hit, “Day Tripper”/”We Can Work It Out,” primarily consisted of mimed studio performances. These performances were often set in somewhat whimsical or unconventional settings and were designed to seamlessly integrate with television programs like “Top of the Pops” and “Hullabaloo.” The T.A.M.I. The show was one of the first concert films released in the mid-1960s, at least as early as 1964.

D. A. Pennebaker’s monochromatic 1965 clip for Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was used in Pennebaker’s Dylan film documentary Don’t Look Back. The clip depicts Dylan calmly shuffling a sequence of enormous cue cards (containing crucial words from the song’s lyrics) in a city back alley, eschewing any attempt to emulate performance or provide a story.

Many other UK musicians, in addition to the Beatles, created “filmed inserts” that could be seen on television when the bands could not perform live. Beginning with their 1965 video for “I Can’t Explain,” The Who appeared in several promotional clips. The band acts like a gang of criminals in the story clip for “Happy Jack” (1966). The tale of how drummer Keith Moon came to join the group is told in the promo film for “Call Me Lightning” (1968): The other three members of the band are drinking tea in what appears to be an abandoned hangar when a “bleeding box” appears, from which a fast-moving time lapse emerges.

Pink Floyd created a range of promotional films, including “San Francisco: Film,” helmed by Anthony Stern, and “Scarecrow,” “Arnold Layne,” and “Interstellar Overdrive,” directed by Peter Whitehead. Notably, Peter Whitehead also directed pioneering music videos for The Rolling Stones during the period from 1966 to 1968.

The Kinks were early trailblazers in the development of promotional clips with narrative elements. They crafted a brief comic film to accompany their song “Dead End Street” in 1966. However, the BBC opted not to broadcast the video, deeming it “in poor taste.”

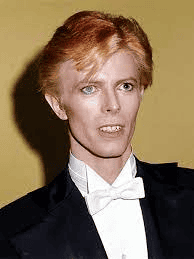

During the early 1970s, David Bowie collaborated with the acclaimed pop photographer Mick Rock, who assumed the role of director for a series of promotional videos. This collection encompassed videos for songs such as “John, I’m Only Dancing,” “The Jean Genie,” the re-release of “Space Oddity” in December 1972 in the United States, and the 1973 single “Life on Mars?”. It’s worth highlighting that the video for “John, I’m Only Dancing” was filmed in a unique setting: an afternoon rehearsal for David Bowie’s performance at the Rainbow Theatre on August 19, 1972. Remarkably, this video was created with an exceedingly modest budget of just $200.

Video: David Bowie – John, I’m Only Dancing

The BBC declined to air the clip, purportedly due to what they perceived as objectionable homosexual implications. As a result, “Top of the Pops” replaced it with a video featuring bikers and a dancer. The “Jean Genie” video was filmed in a single day and edited in less than two days, with a total cost of just US$350. The video alternates between scenes of Bowie and the band performing live and footage of the band in a photographic studio. In the studio shots, they are dressed in black stage attire and positioned against a white backdrop. Additionally, the video includes segments featuring Bowie and Cyrinda Foxe, a friend of David and Angie Bowie and an employee of MainMan, posing provocatively on the street outside the renowned Mars Hotel in San Francisco.

1974-1980: The Beginning of Music in Television

Australian television programs, “Sounds” and “Countdown,” both launched in 1974, played a pivotal role in popularizing the use of promotional film clips for promoting emerging artists and new releases by established acts. They also contributed to the development and proliferation of what would later evolve into the music video genre in Australia and other nations.

In the early months of 1974, Graham Webb, a former radio DJ, launched a weekly television music program aimed at teenagers called “Sounds Unlimited.” It was broadcast on Sydney’s ATN-7 network on Saturday mornings. Later, in 1975, the show underwent a name change, becoming simply “Sounds.” Eventually, it was further streamlined to just “Sounds.”

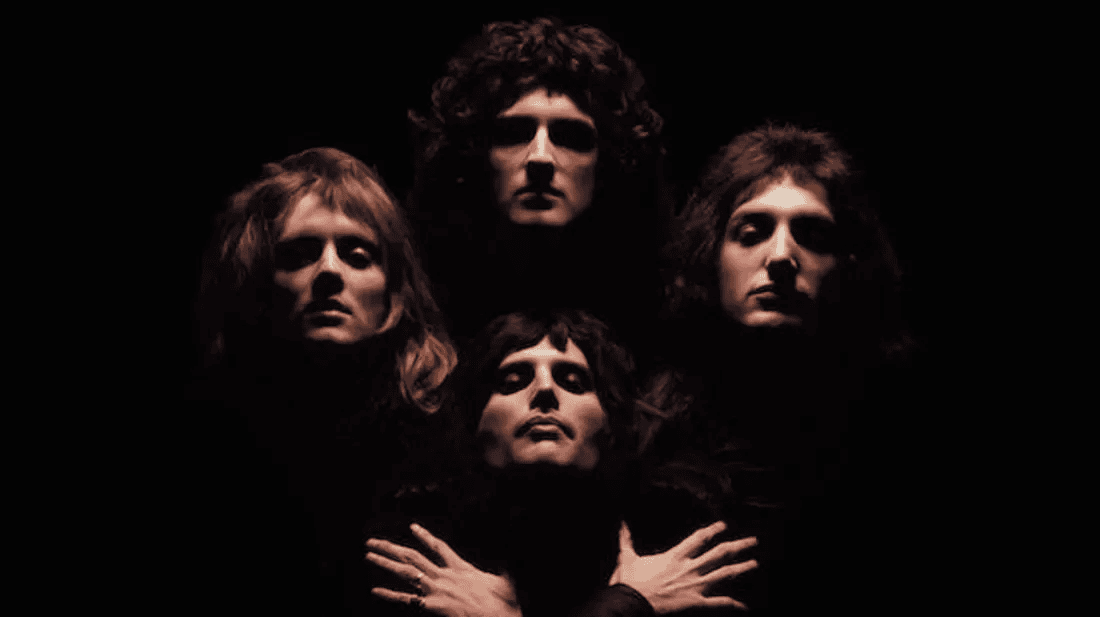

In 1975, Queen collaborated with Bruce Gowers to produce a promotional video for their new single, “Bohemian Rhapsody.” This video made its debut on the BBC’s “Top of the Pops” and is widely recognized as a groundbreaking moment in music history. Rock historian Paul Fowles noted that “Bohemian Rhapsody” is “generally acknowledged as the first global hit single for which an accompanying video played a crucial role in the marketing strategy.”

Video: Queen – Bohemian Rhapsody (1975)

Rolling Stone has emphasized the profound significance of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” noting that it effectively pioneered the concept of the music video, a remarkable achievement that occurred seven years before the launch of MTV.

Split Enz achieved significant success with their single “I Got You” and the album “True Colours” in the same year. Later that year, they embarked on an ambitious project, creating a complete series of promotional videos for every song featured on the album. These videos were directed by their percussionist, Noel Crombie, and were made available for sale on videocassette.

A year after that, The Tubes released “The Completion Backward Principle,” an album that notably contained two videos directed by the band’s keyboard player, Michael Cotten. These videos also incorporated the creative input of Russell Mulcahy, who directed “Talk to Ya Later” and “Don’t Want to Wait Anymore.”

Ex-Monkee Michael Nesmith, who began making short musical films for Saturday Night Live, was among the first to generate music videos. Elephant Parts, directed by William Dear and premiered in 1981, was the first Grammy-winning music video. Billboard credits the independently created Video Concert Hall as the first to broadcast nationwide video music programs on American television.

1981-1991: Music Videos Become Mainstream

In 1981, MTV, a U.S. video channel, made its debut by airing The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star.” This marked the onset of a new era, characterized by round-the-clock music on television. As a result, the music video evolved into a vital component of popular music marketing by the mid-1980s, thanks to this innovative platform. Many of the era’s most renowned bands, such as Michael Jackson, Adam and the Ants, Duran Duran, and Madonna, owed a substantial portion of their fame to the outstanding production quality and alluring charm of their music videos.The arrival of inexpensive and easy-to-use video recording and editing technology and the development of visual effects made with techniques such as image compositing were two significant advances in the development of modern music video. [requires citation] Compared to the comparatively high expenses of using film, the introduction of top-quality color videotape recorders and portable video cameras matched the DIY attitude of the new wave era, allowing many pop groups to produce promotional videos swiftly and cheaply.

Nevertheless, as the music video genre expanded, many directors shifted towards using 35 mm film as their primary medium, although some chose to blend both formats. By the 1980s, the creation of music videos had become a standard practice for most recording artists. This trend even became the subject of satire on the BBC comedy show “Not The Nine O’Clock News,” which produced a spoof music video titled “Nice Video, Shame About The Song.” (The title humorously parodied the popular song “Nice Legs, Shame About Her Face.”)

During this time, directors and the artists they worked with began experimenting with and developing the genre’s form and aesthetic, employing more sophisticated effects, combining film and video, and incorporating a tale or plot into their films. Occasionally, non-representational videos were created where the musical performer was not seen.

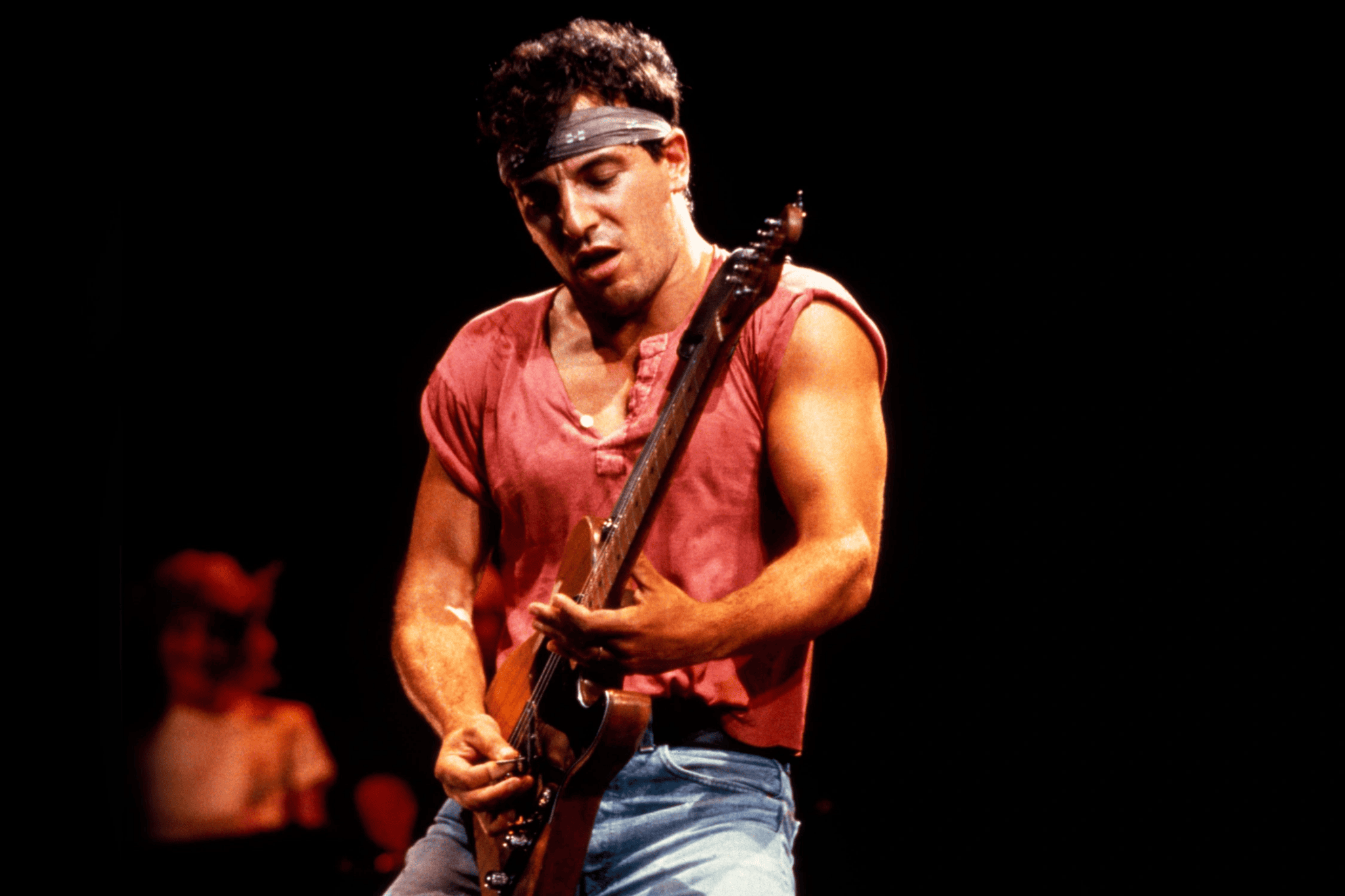

Since the primary purpose of music videos is artist promotion, they are relatively infrequent. A few early 1980s instances include Arnold Levine’s video for Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City,” David Mallet’s collaboration with David Bowie and Queen on “Under Pressure,” and Ian Emes’ creation of Duran Duran’s “The Chauffeur” video. Another noteworthy example is Bill Konersman’s groundbreaking 1987 video for Prince’s “Sign o’ the Times.” This video, inspired by Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” clip, featured only the song’s lyrics and stands out as a later instance of the non-representational technique.

In the early 1980s, music videos started delving into political and social themes. Notable examples include David Bowie’s music videos for “China Girl” and “Let’s Dance” in 1983, both of which tackled issues related to race. Bowie emphasized the importance of using the video format as a means of making social observations rather than merely using it to enhance the public image of the artist. He expressed this sentiment in a 1983 interview, highlighting the significance of using music videos to address broader societal issues.

Video: David Bowie – China Girl (1983)

The approximately 14-minute-long video for Michael Jackson’s song “Thriller,” directed by John Landis, was released in 1983 and became one of the most successful, influential, and famous music videos ever. The video set new production standards, costing $800,000 to make. The video for “Thriller,” as well as Jackson’s earlier videos for “Billie Jean” and “Beat It,” were essential in having African-American artists’ music videos shown on MTV. Before Jackson’s success, MTV rarely aired videos by African-American artists, owing to the cable channel’s initial conception as a rock-music-oriented channel.

However, musician Rick James openly criticized the cable channel, alleging in 1983 that MTV’s refusal to air his song “Super Freak” and videos by other African-American artists amounted to “blatant racism.” David Bowie, in an interview with MTV prior to the release of “Thriller,” expressed astonishment at how MTV overlooked black artists, noting that videos by the “few black artists that one does see” were relegated to late-night time slots between 2:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m. when viewership was minimal.

In addition to this, Glenn D. Daniels played a pivotal role in establishing and founding the country music channel, Music Television (CMT), on March 5, 1983. The channel was created at the Video World Productions facility in Hendersonville, Tennessee. Furthermore, in 1984, Canada saw the debut of the MuchMusic video channel. MTV also made a significant mark by introducing the MTV Video Music Awards (later known as the VMAs) in 1984. This annual awards show became a symbol of MTV’s significance in the music industry. The inaugural event honored the Beatles and David Bowie with the Video Vanguard Award in recognition of their groundbreaking contributions to the world of music videos.

Video: Michael Jackson, Thriller

In 1985, Viacom, the parent company of MTV, established VH1, initially known as “VH-1: Video Hits One.” VH1 offered a milder music selection and was targeted at the slightly older baby-boomer demographic that had grown beyond MTV’s content.

MTV Europe made its debut in 1987, followed by the launch of MTV Asia in 1991. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom witnessed another significant development in music videos with the premiere of “The Chart Show” on Channel 4 in 1986. This show set itself apart by featuring no presenters and presenting an uninterrupted stream of music videos. It became one of the primary outlets for showcasing music videos on British television during that period. To connect the videos, “The Chart Show” utilized cutting-edge computer graphics. In 1989, the show relocated to ITV.

The video for Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” from 1985 was a groundbreaking use of computer animation, and it helped the song become an international smash. The song was a satirical parody of the music-video phenomenon, performed from the perspective of an appliance deliveryman who was both fascinated by and repulsed by the bizarre pictures and people that emerged on MTV. Aardman Animations developed special effects and animation methods for Peter Gabriel’s song “Sledgehammer” in 1986. The video for “Sledgehammer” was a huge hit, winning nine MTV Video Music Awards.

Video: Dire Straits – Money for Nothing

1992 – 2004: Dawn of the Music Video Directors

In November of 1992, MTV initiated the broadcast of music videos directed by a notable group of filmmakers, including Chris Cunningham, Michel Gondry, Spike Jonze, Floria Sigismondi, Stéphane Sednaoui, Mark Romanek, and Hype Williams. Each of these directors brought their unique vision and style to their work. Several of these filmmakers later transitioned into directing feature films, with notable examples being Gondry, Jonze, Sigismondi, and F. Gary Gray. This trend had already been set in motion a few years earlier by directors like Lasse Hallström and David Fincher.

Michael and Janet Jackson’s “Scream,” with an estimated production cost of $7 million, and Madonna’s “Bedtime Story,” reportedly at $5 million, stand out as two of Mark Romanek’s music videos from 1995. These videos are notable for being among the top three most expensive music videos ever made. “Scream” holds the distinction of being the most expensive music video to date.

In the mid to late 1990s, other notable music videos included Walter Stern directing “Firestarter” by The Prodigy, “Bitter Sweet Symphony” directed by The Verve, and “Teardrop” directed by Massive Attack

MTV launched channels around the world around this time to show music videos made in each region: MTV Latin America (1993), MTV India (1996), and MTV Mandarin (1997), to name a few. MTV2, formerly “M2,” launched in 1996 to show more alternative and older music videos. Mariah Carey’s “Heartbreaker,” which cost over $2.5 million in 1999, became one of the most costly films ever made. Billboard sponsored its own Music Video Awards from 1991 through 2001.

Video: Mariah Carey – Heartbreaker

2005 – Present: The Era of Music Videos and Streaming

In 1997, the website iFilm was founded, which contained short videos, including music videos. Between 1999 and 2001, Napster, a peer-to-peer file-sharing program, allowed users to share video files, including music videos. By the mid-2000s, MTV and several of its sister networks had mostly abandoned displaying music videos in favor of reality TV series, which were more popular with viewers and which MTV had helped to pioneer with the 1992 show The Real World.

YouTube was launched in 2005, making internet video viewing considerably faster and easier; similar technology is used by Google Videos, Yahoo! Video, Facebook, and Myspace’s video capabilities. Such websites significantly impacted music video viewing; some artists found popularity due to videos that were largely or fully viewed online. OK Go seized the opportunity presented by the growing trend, gaining fame primarily through the viral success of their music videos for “A Million Ways” in 2005 and “Here It Goes Again” in 2006. These videos initially gained popularity on the internet.

When Apple’s iTunes Store was first launched, it featured a section dedicated to free high-quality music videos that could be watched using the iTunes application. The iTunes Store later expanded to offer music videos for playback on Apple’s iPods with video capabilities.

In 2008, Weezer’s video for “Pork and Beans” embraced this trend by featuring over 20 YouTube celebrities, resulting in the single becoming one of Weezer’s most successful in terms of chart performance.

However, in 2007, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) sent cease-and-desist letters to YouTube users to prevent individual users from distributing videos owned by music companies.

Following its merger with Google, YouTube promised the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) that it would find a way to pay royalties through bulk arrangements with the major record companies. [requires citation] This was complicated because not all labels have the same approach regarding music videos: some welcome the development and post music videos to numerous web venues, seeing them as free advertising for their artists, while others see music videos as the product itself.

In response to their growing emphasis on non-scripted reality programs and other entertainment targeted at a younger audience, MTV made an official decision to remove the “Music Television” tagline from their logo on February 8, 2010. This change was intended to reinforce their shift away from music video airplay and towards other forms of programming.

Vevo – a music video service platform launched by several major music publishers in December 2009, was the first of its kind. The videos by VEVO are also on YouTube, and the advertising revenue is split between Google and VEVO.

Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You” was the most-watched English-language video on YouTube in 2017. Casper’s remix of “Te Bote” featuring Nio Garcia, Darrell, Nicky Jam, Bad Bunny, and Ozuna had the most views on YouTube as of 2018.

Video: Ed Sheeran- Shape of You

Official Lo-Fi Music Video Clips

Around 2006, with the shift towards internet broadcasting and the surge in popularity of user-generated video platforms like YouTube, numerous independent filmmakers started producing live sessions intended for online distribution. Notable examples of this new approach to creating and sharing music videos include Vincent Moon’s work on “The Take-Away Shows,” “In the Van Sessions,” which operated on a similar premise, and the Dutch VPRO 3VOOR12’s initiative called “Behind.” The latter involved recording music videos in unconventional settings like elevators and employing guerrilla filmmaking techniques.

These hastily captured recordings were typically executed on a limited budget and often carried an aesthetic reminiscent of the early 1990s lo-fi music trend. Initially, it served as an essential means for lesser-known indie musicians to introduce themselves to a broader audience, offering an alternative to the growing financial demands of high-production, movie-like music videos. However, this approach has increasingly been embraced by major mainstream artists, including the likes of R.E.M. and Tom Jones.

Vertical Music Videos

In addition to music videos, some artists began releasing alternative vertical videos geared to mobile devices in the late 2010s; these vertical videos are usually platform-exclusive. Vertical videos are frequently seen on Snapchat’s “Discover” section and in Spotify playlists. The number-one songs “Havana” by Camila Cabello and “Girls Like You” by Maroon 5 featuring Cardi B were among the first vertical video releases. Billie Eilish’s “I Don’t Want to Be You Anymore” is YouTube’s most-watched vertical video.

Video: Maroon 5 – Girls Like You

Videos of Lyric

A lyric video is a music video in which the song’s lyrics serve as the main visual element. As a result, they’re relatively simple to make and frequently act as a complement to a more traditional music video.

The words of R.E.M.’s 1986 song “Fall on Me” were interwoven with abstract film imagery in the music video. Prince made a video for his song “Sign o’ the Times” in 1987. The words of the song pulsing to the music were exhibited alongside abstract geometric patterns in the video, which Bill Konersman designed.

Video: Prince – Sign O’ the times

George Michael released a lyric video for “Praying for Time” in 1990. His label released a short clip that put the song’s words on a dark screen because he declined to shoot a regular music video.

Lyric videos became more popular in the 2010s as it became easier for musicians to distribute videos through platforms like YouTube. Many do not include any visuals relating to the performer in question, instead opting for a simple background with the lyrics performed over it. Krokmitn, a death metal band, created “Alpha-Beta,” the first lyric video for a whole album in 2011. Simlev’s style of lettering and images throbbing to the music were utilized in the concept album trailer. The Chainsmokers’ 2016 song “Closer,” which features vocalist Halsey, is the most-watched lyric video on YouTube.

Video: The Chainsmokers – Closer

Censorship in Music Videos

As a music video is both an idea and a means for artistic expression, artists have been restricted on several occasions if their content is judged inappropriate. Due to censorship regulations, local norms, and ethics, what is considered objectionable will vary by country. Usually, an artist’s record label will provide and distribute modified videos or filtered and uncensored films. Music videos have been known to be banned in their entirety in some circumstances because they were deemed far too offensive to be broadcast.

Censorship of Music Videos in 1980s

Queen’s 1982 song “Body Language” was the first video to be banned by MTV. It was ruled unacceptable for a television audience at the time due to thinly veiled homoerotic themes, as well as a lot of skin and sweat (but not enough clothing, save that worn by the fully dressed members of the Queen themselves). The channel did, however, air Olivia Newton-1981 John’s video for the hit song “Physical,” which starred male models exercising in string bikinis who rebuffed her advances before eventually pairing off and walking towards the men’s locker rooms holding hands, though the network cut the clip short right before the quite apparent homosexual ending during some airings. The BBC banned Duran Duran’s video for “Girls on Film,” which featured topless ladies mud wrestling and other representations of sexual obsessions. The video was eventually broadcast on MTV, though substantially modified.

Laura Branigan initially refused an MTV request to edit her “Self Control” video in 1984. Eventually, she gave in after the network refused to air the William Friedkin-directed clip, which featured the singer being dragged through a series of increasingly passionate, if increasingly stylized, nightclubs by a masked man who eventually takes her to bed. Cher’s “If I Could Turn Back Time” video (in which she sings in a body suit surrounded by a ship full of adoring sailors) was limited to late-night MTV broadcasts in 1989. The BBC banned The Sex Pistols’ video for “God Save the Queen” because it was “in terrible bad taste.”MTV banned “Mötley Crüe’s video for “Girls, Girls, Girls” as it featured entirely naked women dancing around the band members at a strip club, but the band later produced a different version that MTV accepted.

In 1983, a feature on censorship and “Rock Video Violence” aired on Entertainment Tonight. The MTV rock video violence that had an impact on early 1980s teenagers was investigated in this episode. The likes of Duran Duran, Michael Jackson, Kiss, Golden Earring, Kansas, Billy Idol, Def Leppard, Pat Benatar, and The Rolling Stones all had music videos that were screened. The National Coalition on TV Violence’s Dr. Thomas Radecki was interviewed, criticizing the fledgling rock video industry of excessive violence. The work of recording artists John Cougar Mellencamp, Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley of Kiss, and directors Dominic Orlando and Julien Temple was defended. The end of the program was that the dispute would continue to develop. Certain artists have used censorship as a form of publicity. Because Top of the Pops was censorious about video content in the 1980s, some artists prepared videos they knew would be restricted, then used the public outcry to promote their release. Duran Duran’s “Girls on Film” and Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax,” directed by Bernard Rose, are two examples of this strategy.

Censorship of Music Videos in 1990s

Michael Jackson’s “Black or White” dance portion was cut out in 1991 because it showed Jackson “inappropriately” touching himself. MTV, VH1, and the BBC all banned his most controversial video, “They Don’t Care About Us,” due to purported anti-Semitic overtones in the song and the imagery in the background of the “Prison Version” of the video.

Madonna is the artist most linked with the censorship of music videos. The criticism over Madonna’s sexuality marketing began with the video for “Lucky Star” and grew over time as clips like “Like a Virgin” were released. The subject matter (teenage pregnancy) presented in the video for the song “Papa Don’t Preach” sparked outrage. Due to its religious, sexual, and racially charged themes, “Like a Prayer” drew a lot of flak. The music video song of Madonna for the song “Justify My Love” was also banned by MTV in 1990 after facing media backlash over its depiction of sadomasochism, homosexuality, cross-dressing, and group sex. In Canada, the controversy surrounding the music video network MuchMusic’s decision to remove “Justify My Love” led to the launch of Too Much 4 Much in 1991, a series of late-night specials (which were still broadcast in the early 2000s) in which videos officially banned by MuchMusic were broadcast, followed by a panel discussion about why they were removed.

The BBC banned The Shamen’s video for “Ebeneezer Goode” in 1992 because it was deemed to be a subliminal endorsement of the recreational drug Ecstasy. [64] Due to representations of drug usage and nudity, the Prodigy’s 1997 video for “Smack My Bitch Up” was prohibited in various countries. The BBC rejected The Prodigy’s video for “Firestarter” because it contained references to arson. [65]

MTV banned the Australian rock band INXS’ song “The Gift” in 1993 because it included videos from the Holocaust and the Gulf Conflict, as well as scenes of poverty, pollution, war, and terrorism. In addition, MTV rejected Tool’s music video for “Prison Sex” because it contained child abuse.

Censorship of Music Videos in 2000s

Robbie Williams’ music video for “Rock DJ” in 2000 sparked outrage owing to its gruesome nature, which shows Williams stripping naked, peeling off his skin to reveal raw flesh, then tearing off his muscles and organs until he becomes a blood-soaked skeleton. In the United Kingdom, the video was censored during the day and broadcast uncut after 10 p.m. Due to satanic charges, the video was prohibited in the Dominican Republic.

Björk’s “Pagan Poetry” video was banned from MTV in 2001 due to portrayals of sexual intercourse, fellatio, and body piercings.

The music video for “All the Things She Said” by T. A.T.u 2002 sparked outrage since it portrayed two young Russian girls, Lena Katina and Yulia Volkova, hugging and kissing. Richard and Judy, British TV hosts, attempted to have the film banned, stating that the use of school uniforms and young girls kissing appealed to ‘pedophiles,’ but their effort was unsuccessful. The kiss was planned into their live performances to capitalize on the outrage. The girls’ performance was broadcast on Top of the Pops, but the kiss was substituted by audience footage. The Tonight Show with Jay Leno on NBC pulled away from the girls kissing and instead showed pictures of the band.

The video for Maroon 5’s “This Love” sparked controversy in 2004 because of personal scenes between frontman Adam Levine and his then-girlfriend. Even though those scenes were taken at strategic angles, an edited version was released with a stream of computer-generated flowers to cover up even more. Because of its violence and sexual themes, Marilyn Manson’s video for “(s)AINT” was banned by their label. The next year, Eminem’s music video for “Just Lose It,” a spoof of Michael Jackson’s 2005 child abuse trial, plastic surgery, and hair catching fire while filming a Pepsi commercial, sparked outrage.

Due to Muslim moral perspectives, the Egyptian government censorship committee prohibited at least 20 music videos with sexual undertones as of 2005. Jessica Simpson’s music video for “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,’ ‘ in which she played Daisy Duke, was controversial since it featured Simpson in “revealing’ ‘ clothes and cleaning the General Lee car in her bikini. As a result of the issue, the music video was prohibited in various countries.

While country music has mainly avoided criticism over video material, it has never been completely free of it. The music video for Rascal Flatts’ song “I Melt” from 2003 is an example, with clips of guitarist Joe Don Rooney’s bare buttocks and model Christina Auria taking a nude shower earning prominence. The video was the first on CMT to feature nudity, and it became the network’s “Top Twenty Countdown” program’s #1. When the group refused to produce an altered version, GAC banned the video.

Censorship of Music Videos in 2010s

The video “Hurricane” by Thirty Seconds to Mars was restricted in 2010 owing to its primary themes of violence, nudity, and sex. Later, a clean version of the short film was made that could be broadcast on television. The explicit version, which has an 18+ viewing certificate, is available on the band’s official website.

BET banned Ciara’s video for “Ride” because it was too sexually charged, according to the network. All UK television broadcasters likewise afterward banned the video.

The video for “S&M,” which includes Rihanna flogging a tied-up white man, holding hostages, and a lesbian kiss, was banned in almost a dozen countries and marked as inappropriate for viewers under the age of 18 on YouTube in 2011.

Commercialization of Music Videos

Video Albums

Music videos have been made available for commercial distribution in a range of formats, including Laser Disc, videotape, Blu-Ray, and DVD, among others. A video album, much like an audio album, collects several music videos onto a single disc. However, it’s worth noting that the market for video albums is relatively smaller when compared to that of singles and audio albums. To qualify for gold certification from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), record companies are required to deliver 50,000 units of video albums to retailers. In contrast, audio albums and singles must ship 500,000 units to attain gold certification.

One of the earliest video albums was “Eat to the Beat” (1979), a video cassette that featured music videos for each track from Blondie’s fourth studio album of the same name. It was directed by David Mallet and produced by Paul Flattery for Jon Roseman Productions. These music videos were filmed in New York and New Jersey, some depicting the band performing live and others portraying scenarios inspired by the song lyrics. Another well-known video album was “Olivia Physical” (1982) by Olivia Newton-John, which won Video of the Year at the 25th Grammy Awards. This video compilation featured all the tracks from her ninth studio album, “Physical.”

On March 30, 1985, Billboard magazine introduced the weekly best-selling music video sales chart in the United States, known as the Top Music Videocassette Chart, in response to the growing popularity of video albums (now referred to as the Music Video Sales Chart). Tina Turner’s “Private Dancer” (1984) became the first chart-topper, featuring four music videos on a video cassette.

In the United Kingdom, a similar chart was launched by the Official Charts Company on January 30, 1994, with Bryan Adams’ “So Far So Good” debuting at number one.

As per the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), the Eagles’ “Farewell 1 Tour-Live from Melbourne” (2005) has achieved the highest certification for a long-form music video, boasting a 30-time platinum certification, which signifies the shipment of three million units. In a similar vein, the Rolling Stones’ “Four Flicks” stands as the top-certified music video set, securing a 19-time platinum certification.

Video Single

A video single refers to a format typically available on videotape, LaserDisc, or DVD, containing no more than three music videos. The British synthpop band, The Human League, made history by releasing the very first commercial video single titled “The Human League Video Single” in 1983, which was made available on VHS and Betamax. However, due to its relatively high price of £10.99, in contrast to the approximately £1.99 cost of a 7″ vinyl single, it did not achieve significant commercial success.

Madonna later played a pivotal role in elevating the profile of the video single format. In 1990, she released “Justify My Love” as a video single, leading to increased mainstream recognition of VHS singles. It’s worth noting that “Justify My Love” remains the best-selling video single of all time, even after all these years.

A video single refers to a format typically available on videotape, LaserDisc, or DVD, containing no more than three music videos. The British synthpop band, The Human League, made history by releasing the very first commercial video single titled “The Human League Video Single” in 1983, which was made available on VHS and Betamax. However, due to its relatively high price of £10.99, in contrast to the approximately £1.99 cost of a 7″ vinyl single, it did not achieve significant commercial success.

Madonna later played a pivotal role in elevating the profile of the video single format. In 1990, she released “Justify My Love” as a video single, leading to increased mainstream recognition of VHS singles. It’s worth noting that “Justify My Love” remains the best-selling video single of all time, even after all these years.

DVD singles are extremely frequent in the United Kingdom, where up to three physical formats are eligible for the chart (with the single available on DVD, CD, and vinyl record). Like other single formats, DVD singles have a limited production run, making them valuable collector’s goods. Because when artists began releasing them in the early 2000s, the CD single began to decline, the DVD single never achieved high success in the United Kingdom. They were also thought to be pricey. Some musicians would rather use music videos as added features on a CD single or album than release DVD singles.

Artists in Japan have been able to release singles in the CD+DVD format since the early 2000s. Ayumi Hamasaki, a Japanese singer, has been dubbed the “founder of the CD+DVD format,” with her 2005 single “Fairyland” serving as an example. The CD+DVD format is way more expensive and typically includes one or more music videos and a “making of” portion or other supplementary content.

Video: Ayumi Hamasaki – Fairyland

Hello! Project, a Japanese music conglomerate, published DVD singles for practically all of its CD single releases. They’re referred to as Single Vs by the company. A music video for the title song, as well as various other versions of the song and a making-of, is normally included in a Single V. Hello! Project fan club events, an Event V will occasionally be produced with different shots of a promotional video or supplementary footage, such as exclusive backstage footage or film from a photoshoot. As of 2017, Single Vs are no longer available; instead, Hello! Project acts now include music videos on DVDs with their limited edition CD singles.

Unofficial Music Videos

Unofficial, fan-made music videos (sometimes known as “bootleg” cassettes) are often created by synchronizing footage from other sources, such as television shows or films, with the song. Kandy Fong developed the first known fan video, or Songvid 1975, utilizing still images from Star Trek placed into a slide carousel and played with a song. Soon after, videocassette recorders were used to create fan videos. In the late 1990s, fan-made videos became more popular due to easy internet dissemination and inexpensive video-editing software. The Beatles Blu-ray disc contained a Flash animation for the song “Come Together” by the Beatles in 2016.

In 2004, a South African Placebo fan created a claymation video for the band’s “English Summer Rain” song and emailed it to the band. They were so pleased with the outcome that it was put on their best hits DVD.

What Do You Need for a Music Video?

Here’s a detailed breakdown of what you need for a music video:

Concept and Storyboard

Start with a creative concept that complements the song’s theme or message. Develop a storyboard or shot list to outline the video’s visual sequences and transitions.

Song

The music track serves as the foundation. You’ll need the final audio mix or master of the song to synchronize with the video during editing.

Location and Set

Choose suitable locations or set designs that align with the video’s concept. Ensure you have permissions and permits for shooting at these locations, if required.

Crew

Assemble a skilled team, including a director, director of photography (DP), camera operators, lighting technicians, production assistants, makeup artists, and costume designers. The size of your crew depends on the video’s complexity.

Cast

Depending on the concept, you may need actors, dancers, or performers to appear in the video. Hold auditions if necessary to find the right talent.

Equipment

High-quality cameras, lenses, and other equipment are essential. Consider factors like camera stabilizers, drones for aerial shots, and lighting kits to ensure professional-quality visuals.

Costumes and Wardrobe

Collaborate with costume designers and stylists to choose attire that suits the video’s concept and enhances the visual appeal.

Makeup and Hair

Hire makeup artists and hairstylists to ensure that performers look their best on camera.

Props and Set Dressing

Acquire any necessary props, furniture, or set decorations to enhance the video’s storytelling.

Budget

Develop a budget that covers all expenses, including pre-production, production, and post-production costs. Ensure you have adequate funding to execute your vision.

Permits and Insurance

Obtain any required permits or insurance for shooting in public locations, ensuring legal compliance.

Timeline and Schedule

Create a detailed shooting schedule that outlines the shooting days, locations, and scenes. Factor in time for rehearsals, setup, and teardown.

Safety Measures

Implement safety protocols to protect the cast and crew during filming, especially for stunts or challenging sequences.

Post-Production Team

Plan for the post-production phase, including video editing, color grading, sound mixing, and visual effects. Hire experienced editors and post-production professionals.

Editing Software

Invest in professional video editing software like Adobe Premiere Pro, Final Cut Pro, or DaVinci Resolve for editing and post-production work.

Music Licensing

If using copyrighted music, obtain the necessary licenses or permissions to avoid legal issues related to copyright infringement.

Distribution and Promotion

Develop a strategy for promoting the music video once it’s completed, including uploading it to platforms like YouTube, Vevo, or Vimeo.

How to Find a Music Video through Searching on the Web?

It is aggravating to have a music video stuck in your head with no idea what it’s called or what song it is related to. You recall picture sequences but have no idea how to make sense of them. You become increasingly upset and annoyed with yourself as time passes for not remembering!

If you’re reading this, you are probably going through the same thing right now. We’ve got some excellent news for you: we are here to assist you. Here are a few suggestions for finding a music video by describing it.

Write a Few lyrics in the Search Box

If you recall a few phrases from the song featured in the video, type them into Google and press the search button. If any of the lyrics are correct, Google will present you with a list of the most relevant results that you can scroll through.

You can also use the sophisticated search methodology indicated in the fourth step to customize your search results. If this doesn’t work, don’t worry; just move on to the next step.

Search on Youtube

YouTube is another simple approach to finding a music video by describing it. We don’t mean merely typing into the search bar and pressing Enter when we say “YouTube search.”

You may be surprised to learn that sophisticated search operators can help you refine and narrow your YouTube searches for more accurate results. Date, type, duration, and features are examples of these operators. Add quotes to the beginning and end of your keyword if you want your search results to include the exact words you searched for.

Utilize the “Filter” button to refine your search results and obtain more precise outcomes. Just enter your search query in the search bar and click on the Filter button. You’ll have the option to apply various filters to assist you in pinpointing your desired content.

Filters such as “Features” and “Duration” have proven to be particularly valuable when seeking out YouTube videos that may have been elusive for some time!

Post it on a Song Naming Community

If you can’t find the music video on Google or YouTube, try posting on Facebook’s song naming forums, Reddit, or dedicated websites like Wat Zat Song. We advocate joining active communities since they will help you achieve your goals faster. Even if the community members cannot recognize the songs, they may be able to suggest some advanced programs to assist you.

However, make an effort to be as specific as possible. You may, for example, try detailing the sequences and lyrics. You can also describe what sections of the music video you remember from the one you’re looking for.

Try describing the characters from the music video in the description if you recall them. Furthermore, if you recall the date of its publication, including that information can be beneficial.

Use Advanced Google Search

However, make an effort to be as specific as possible. You may, for example, try detailing the sequences and lyrics. You can also describe what sections of the music video you remember from the one you’re looking for.

Try describing the characters from the music video in the description if you recall them. Furthermore, if you recall the date of its publication, including that information can be beneficial.

Utilize a Song Identifier App

Song identifier apps, as the name implies, are designed to assist users in locating their favorite songs and music videos.

Unlike most search engines and apps, song identification apps let you find your selected song simply by humming into the microphone. All you have to do in most song identifier apps is tap the “Search a song” button. In some apps, you may need to tap the microphone icon and say, “What is this song?”

Wait for the results after activating the mic and humming the song for 10–15 seconds.

SoundHound is one such tool. You may also utilize Google Assistant to locate the song you seek. “Hey Google, what’s this song?” is all you have to say for a few seconds, and hum

If the search engine recognizes your voice, you will be routed to the page you are looking for.

Look up the Artist’s Discography

We remember the artist but not the song most of the time.

If true, looking up the artist’s name can help you find your desired music. You can use search engines to learn more about the artist, and the artist’s Wikipedia page may also be useful.

You can also check out their Spotify and Apple Music pages, as all their tracks will likely be available there. Furthermore, if you recall the actors’ names in the music video, you can look for them individually. You might be able to find the required video by looking for music videos in which they have appeared.

Why Are Music Videos Still Relevant?

Some argue that the quality of music videos has deteriorated since both large sums of money and MTV abandoned the genre, but music videos as an art form are as essential now as ever. They are part of our visual language and an important component of the culture of our music, art, and entertainment consumption… They are also a fun way to while away five minutes in the afternoon.

YouTube is the second most popular search engine after Google and the world’s largest streaming music service; finding new music videos is simple. The issue, unlike MTV, is that there is under-curation in an oversaturated market. It’s easier than ever to make and upload a video to the internet, which is fantastic. However, just because anyone can make a video does not imply they’re good, and what does GOOD mean? That, of course, depends on who you are asking.

On the internet, music is consumed and forgotten daily, if not hourly. So, from a record label perspective, an artist needs something more than an MP3 to get noticed. They require great creative images to have a significant competitive advantage. Take a look at FKA Twigs and Tyler The Creator, two musicians who have made their visual effects as strong as their musical ones.

Music videos are an important aspect of an artist’s overall artistic vision. A music video is a focus point – it catches your attention, or at least helps, since that music can be streamed anytime and everywhere. Due to how we now consume music, music videos have become just as significant, if not more so, than artwork. We used to buy a physical CD with a beautiful cover, but now we listen to music via various platforms.

A video establishes a connection between an artist and a listener, as well as a listener and an audience. They are a crucial medium for contemporary pop culture and technology in many ways. Fashion fads like Pharrell’s hat and dancing trends like The Dougie created cultural hits faster and more accessible than TV and movies at the time. Who could forget Miley Cyrus?

A terrible video can kill a song’s life, while a good video can turn it into a hit. Take DJ Snake’s Turn Down For What, for example. The music had been out for a while, but it was not until The Daniels directed the video that it became a full smash. Another notable example is Gangnam Style, which left the audience remembering the music after watching the video.

This brings us perfectly into the realm of a production company and a director. After the success of Turn Down For What, the directors went on to make several wacky, unconventional short films and have just premiered their first feature picture at Sundance. A music video is unlike any other short-form medium in that it can reach millions upon millions of people.

Short films rarely have the same reach as music videos and frequently require self-funding, whereas a music video has (some) funding. However, certain directors, such as Kahlil Joseph, have made films transcending the music video genre, such as his m.A.A.D. Film for Kendrick Lamar or his film for Flying Lotus, which received the Sundance short film award.

Music videos are still great for directors to sharpen their skills and express their creativity. They provide opportunities for fresh people to enter many sections of the film industry — and they are still a way in. The media still use music videos to uncover fresh talent, and those concepts are then adapted to various other things. Take Bonnie Prince, for example. The method used in Billy’s video Bonnie, directed by Harmony Korine, was utilized in a Thorntons chocolate ad.

Many directors began their careers making music videos before moving on to filmmaking; examples include Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, and, more recently, Daniel Wolfe. These visionary filmmakers would not be creating the fascinating and experimental work they are now if music videos didn’t exist. It’s a source of inspiration regardless of where you’re at in your profession – they will always pique people’s interest.

There shouldn’t be too many rules if you have a savvy artist and record label – music videos can push the boundaries and be works of sheer ingenuity. Budgets have shrunk, but good creativity will triumph – just look at Plastic Zoo’s Eagulls video. It was shot for pennies on the dollar and depicts a brain slowly deteriorating. That’s fantastic, and it’s even better that it got an NME award for best video. Take, for example, Tangerine, a full film shot entirely on one iPhone. But enough about me; let’s return to music videos and the future.

Video: Eagulls – Nerve Endings

We all demand shorter, snappier content as millennials, and I have to admit that, despite watching videos as part of my profession, I’m guilty of scrolling through many of them. Music videos will continue to exist, with the best ones surviving. Still, there will be an increase in the evolution of shorter bits of music video content adapted to various mediums. What exactly is a music video? A much broader definition will be used. Music video material created expressly for Snapchat, Instagram, and Periscope will be seen. One apparent issue is that an artist will have even more content to add to what is already overwhelming to an audience. Still, services like Apple Music and Spotify will provide better curation by creating video show channels, similar to what Beats Radio has done.

Spotify is now producing its video content for its platform, reversing the YouTube trend. Because Spotify recognizes the importance of images in audio and the fact that the two go hand in hand, we will see more music videos created on these platforms. Music videos and virtual reality will become more integrated, accessible, and thus more creatively stimulating as technology improves. Inside a streamlined financial environment, there will be more and more options for integrated branding within music videos. But that is a different tale altogether.

Five Ways to Improve Your Music Videos

Improving music videos involves enhancing visual and storytelling elements to captivate and resonate with the audience. Here are five important ways to achieve that:

Engaging Concept

Start with a compelling concept or storyline that complements the song’s lyrics and evokes emotions. A well-thought-out narrative adds depth to the video.

Creative Cinematography

Experiment with camera angles, lighting, and composition to create visually stunning shots. Dynamic cinematography can elevate the video’s overall quality.

Effective Editing

Ensure seamless editing, synchronization of visuals with music, and tight pacing to maintain viewer interest throughout the video.

Visual Effects

Incorporate relevant and well-executed visual effects to enhance the video’s storytelling and aesthetics.

Artistic Direction

Develop a distinct visual style that aligns with the artist’s brand and genre while pushing creative boundaries.

Most Viewed YouTube Videos

Video: Learning Colors – Colorful Eggs on a Farm

Video: Masha and The Bear – Recipe for Disaster (Episode 17)

Video: Phonics Song with Two Words – A for Apple

Final Thoughts

Since their inception, music videos have only grown by leaps and bounds. The medium for the music videos has changed. There was a time when you had to conjure up a lot of patience to wait for your favorite song to be played on television. In today’s times, you must tap your mobile phone screens to watch your favorite music videos. The mediums might continue to change, but music videos are here to stay.