A screenplay, often known as a script, is writing created by screenwriters for a film, television show, or video game. These screenplays can be originals or adaptations of previously published material. The characters’ movements, actions, expressions, and dialogues are also described in them. A teleplay is a screenplay explicitly produced for television.

What is a Screenplay?

A screenplay or movie script is the blueprint for any feature film, television show, or video game. Character actions, language, movement, and stage direction are all included in the scripts. The scriptwriting format used in a movie script has its own set of industry-standard norms, which varies slightly from the scriptwriting style used in a shooting script. A shooting script is a more precisely formatted version of the pre-production and production script to transform the screenplay into a movie. Camera directions, music cues, and transitions can all be included in this version.

Features of a Screenplay

Font Size

A courier typeface in size 12 is required for screenplays. People in the film and television industries have chosen this size and typeface for readability over the years. It also provides a decent method for estimating the length of the film.

Page Numbers

Page numbers are present at the top of the right margin on a page. The numbers are followed by a period. The only pages without a number are the title page and the first page.

Page Margins

The top and right margins are each set to one inch. The bottom margin is a quarter-inch wide, while the left margin is 1.5 inches wide.

Formatting a Screenplay

The Importance of a Screenplay Format

It is not only a matter of style, and the “rules” aren’t made up on the spot. Throughout the filmmaking process, the industry-standard script format has numerous purposes and advantages. A draft written in the correct screenplay structure conveys professionalism; otherwise, it appears amateurish and is likely discarded before page one.

The script breakdown process, one of the most critical processes in turning a screenplay into an actual film, is also aided by proper cinema script format. Screenwriting format influences both film budget and shooting schedule creation.

Most authors use specialized screenplay writing tools like Final Draft rather than manually replicating these movie script format standards. This eliminates all guesswork and allows the writer to concentrate on what matters most: the tale you’re attempting to tell.

Quick Start Guide: Final Draft 12 – YouTube

This will be a lot easier if you choose a suitable screenplay format. It is critical to use these elements correctly to write a script properly. From tiny film scripts to multimillion-dollar blockbusters, this is true.

You can read and download over 250+ scripts in Nashville Film Institute’s script scene example collection for more research into how experienced screenwriters manage screenwriting format. Now, let’s look at some of the key features found in screenwriting.

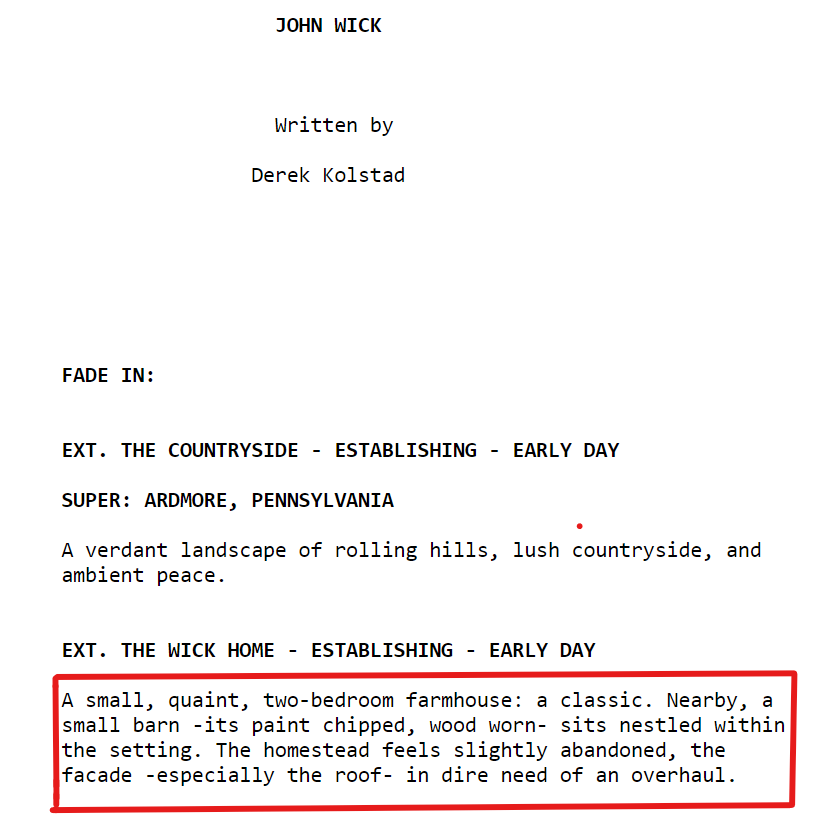

Slugline

Slug Lines (also known as scene headings) indicate where the action occurs in the story. It looks somewhat like this: a place, followed by a time.

In this screenplay example, the scene begins in this Kitchen, but what does INT signify in a script? When it comes to sluglines, the first step is to determine whether the scenario is set inside (INT.) or outdoors (OUT). (EXT.) Then include the scene’s location and the time of day (Day, Night, Morning, Evening, etc.).

Mark a scene as “continuous” in the time slot if it directly follows the preceding scene. If the time difference is only a few minutes, feel free to put “moments later” in your slug line.

There are instances when you will have a scene that takes place both inside and outside. The majority of the time, this will take place in a moving car. Start your slugline with “INT./EXT.” in those circumstances. If you are using screenwriting software, it will format it for you, but if you are doing it by hand, make sure the entire slugline is written in ALL CAPS.

Once again, you can have a look at Nashville Film Institute’s screenplay library. Sluglines are crucial since they are how assistant directors and line producers show how you will shoot things.

For hair, makeup, and costume departments, the difference between one scene being night and the next being day is critical for continuity. That’s why it’s one of the essential aspects of the movie screenplay format: it shows you when and where a scene occurs in the overall plot. Knowing what time it is and where the scene takes place has a significant impact on practically every department.

Action Lines

Your action lines should be placed directly beneath the slugline. Screenplays must always be written in the present tense and should be as visually descriptive as possible. In a screenplay, here’s an example of action lines in script format. It is worth noting that the actions are presented in a plain and accessible manner as “simply the facts.”

Action lines, in particular, inform the reader about what they will see and hear in the finished picture aside from language. Also, don’t take the word “action” too literally; this category includes everything, including combat scenes. Watch as we show you how to script a battle scene like John Wick in just 5 minutes in this video.

When it comes to screenplay format, remember that a script is a document that will be transformed into a movie, not something that can be read on its own.

Department heads are prone to taking things literally and, in many cases, without questioning them. So if you put anything stupid in the description, they’ll figure out a way to make it genuine – after all, that’s their job. Make sure your action lines are deliberate and exact. Find a happy medium between letting a filmmaker guide a scene and providing enough information to the Propmaster to exactly obtain what you want.

This is especially true if you’re trying to write anything as hectic as a fight scene or a pursuit scenario when you must meticulously plot every aspect. The more sophisticated the product, the more critical it is that you stick to the script format. This is why we have the screenplay structure created in the first place.

In screenplay format, there are two hard and fast capitalization rules. First, when a character’s name appears for the first time in an action/description, capitalize it and screenplay the transitions.

You can also use critical objects, sound design, and camera movements to your advantage. You can utilize the movie script format to attract attention to anything essential enough to warrant the attention of people breaking down the script. Just be careful not to overdo it. Nothing is more irritating and perplexing than when someone CAPITALIZES EVERYTHING ON THE PAGE AT THE SAME TIME.

Character Cues

When a character speaks after the action/description, we begin with their name. Then, you insert a conversation behind a character ID that is centered and capitalized. Your character ID does not have to be your complete name. It could be a first or last name, as well as an alias. Whatever best describes the character’s personality. And be consistent – if a character is introduced as “McCloud,” he stays that way, even if his first name is revealed to be “Jack.”

The only exception is if your character wears a disguise, especially if they imitate a voice while doing so. “Bruce Wayne,” for example, would be this guy.

While this individual would be “Batman.”

Although they are the same individual dressed in different garb, another option is to use a slash if that’s too much for you. For example, when Bruce Wayne is Batman, he becomes “Bruce Wayne/Batman,” and he is just Bruce Wayne when he doesn’t take the role.

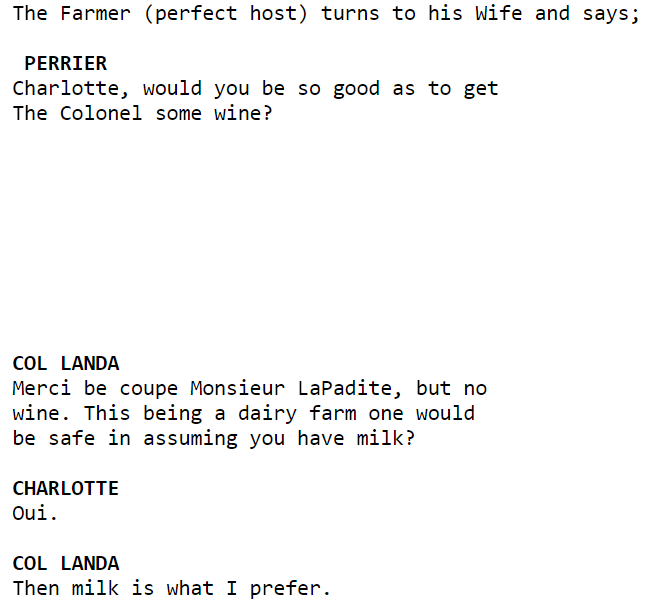

Dialogue

The conversation is straightforward. In terms of formatting, at least. But, of course, writing effective dialogue is a topic in and of itself.

This is how the dialogue appears in a screenplay. The discussion is kept to the middle of the page by the margins on both sides. This creates white space on the page, which you can use for notes. To demonstrate how to format dialogue in a script, look at the sample screenplay from Inglourious Basterds below:

The goal is to let the characters speak for themselves when crafting conversation. But, of course, the fact that you, the writer, are shaping those characters is always front and center. As a result, adopting software that handles screenplay formatting automatically allows you to focus on the characters and their lines.

Extensions

Extensions appear in parenthesis next to a character’s name and describe how the audience hears the discourse. When you start entering the parenthesis, most screenwriting tools will automatically give the usual screenplay format extensions.

1. Continued (CONT’D)

You will also see (CONT’D) next to a character’s name to indicate that their lines will continue after being “interrupted” by action or description. You can see it in action below from the movie Mission Impossible: II

2. Voice-Over (V.O)

When a character speaks in the scene and is not heard by others, this is known as a voice-over. Usually, narration can also be an interior monologue of the character. For example, you can see the use of V.O. in the movie “V for Vendetta.”

3. Off-Screen (O. S)

When a character is speaking, other characters can hear them, but the audience or other characters can’t see them. So write (O.S.) next to the name of the character. It’s also okay to write “off-camera” as (O.C.).

The extension includes the following:

- Over a loudspeaker, someone is making an announcement.

- A character who makes a spectacular and unexpected arrival.

- A phantom voice – disembodied.

The example given below is from the movie “Dances with Wolves.”

The use of O.C. can be seen in an excerpt of the movie’s script, “Next.”

4. INTO DEVICES

Characters converse on their phones or radios instead of chatting with each other face to face. This is especially useful when characters are on the phone and talking to someone directly next to them. Or when a local news station lays out the story’s exposition.

5. Pre-Lap

The pre-lap conversation is dialogue from the following scene that begins before the current scene ends. Write “pre-lap” next to the character’s name in parentheses. The example below from the movie “Hitchcock” shows how Pre-Lap is used in screenplays.

Parentheticals

At first look, parentheticals may appear to be extensions, but there are a few crucial differences. Extensions are technical directions that describe the location of the actor speaking the dialogue in the scene.

Parentheticals are instructions to the actor that explain how to deliver the sentence.

An example of a parenthetical in an appropriate screenplay format is shown below. This is the most depressing sequence in the movie Marriage Story. Take note of how writer/director Noah Baumbach employs parentheticals to depict his characters’ internal strife. Make sure to read the entire scenario to understand how Baumbach creates a multi-layered and emotionally complex situation by combining conversation and parentheticals.

Parentheticals are placed directly beneath the character ID in the script format (parentheses). Here are a few examples:

- Loudly

- Painfully

- Tearfully

- Murmuring

- Giggling

Actions for the performers to execute while speaking can likewise be included in parentheticals. When writing for television, where page space is limited, this is very common.

- Shrugging

- Strengthening

- Falling to Knees

When composing parentheticals in screenwriting software, it is critical to modify parts. You cannot just put them in parentheses and hope they will make sense.

Screenplay Transitions

Screenplay transitions are on the far right of the page and positioned between two scenes to show how an editor should switch between them. These are typically capitalized in proper screenplay structure.

Instead of marking everything with a “CUT TO:” use screenplay transitions just when you want it to stand out. For example, in this scene from Ocean’s Eleven, writer Ted Griffin employs this transition to underline the shift in setting to Las Vegas.

Note how the dialogue and description create momentum leading up to the following scene, which is interrupted by the “CUT TO:” transition and ends with a lively depiction of Sin City. Knowing how to structure a screenplay includes understanding how to employ screenplay transitions. Most editors nowadays, however, are aware that no transition signals a normal cut. The “CUT TO:” is also commonly used to indicate the end of a scene in Multicam television scripts. Because Multicam scripts have page breaks for both scenes and acts, it’s crucial to distinguish between when a scene ends and when an act breaks, which is also a commercial break.

Your screenwriting program will most likely include the other typical screenplay transitions installed for you, just like parentheticals. Among them include, but are not limited to:

Smash To

This is a ten-fold increase in the speed of a “CUT TO:” command. In the middle of a sentence, this type of cut occurs. The example of the usage of “Smash To” in Twilight is a good example.

DISSOLVE TO

When one scene “dissolves” into another, almost wholly converts into it. This is usually used to denote the passage of time. This example from the script of Twilight is a prime example.

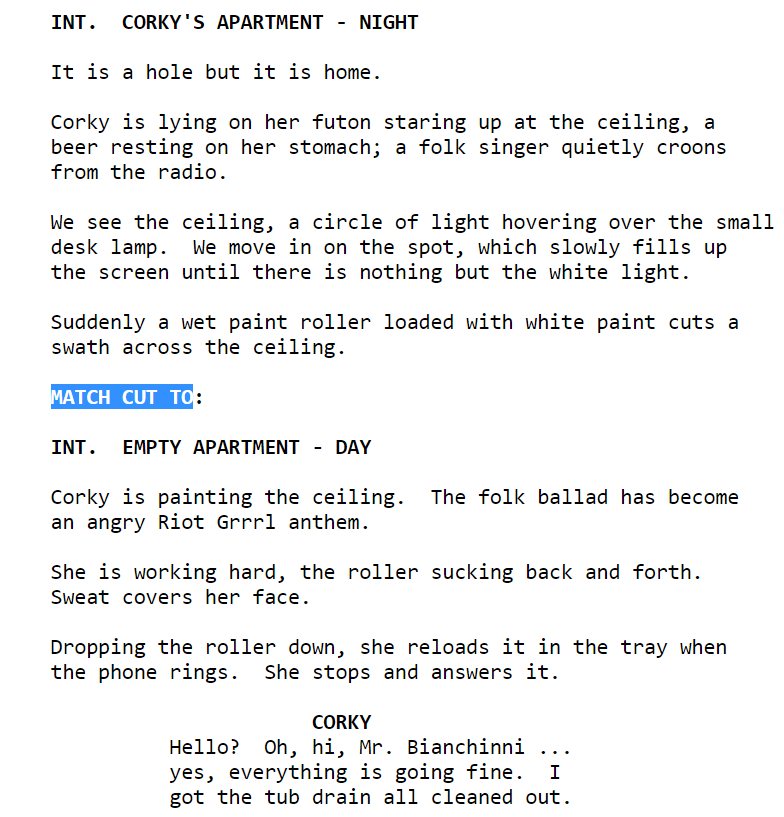

MATCH CUT TO

Cutting the film so that the last shot in the previous scene matches the first shot in the new scene is a challenging edit. To understand how match cuts are written, here is an example of how and when they are utilized in movies.

INTERCUT

When you intercut (or cross-cut) between two different scenes, it is known as cross-cutting. It is frequently, but not always, used for phone calls. The example given below from the script of “King Kong” highlights how the INTERCUT is used.

Sub-Headers

Subheaders function as mini-sluglines, indicating a different location or time inside a scene. They are even capitalized and left-justified, just like sluglines. Take a look at this sample to see what we’re talking about:

You will probably have to format it as a “scene header” if you are using screenwriting software – that is great!

A subheader may be used to show a shift in rooms if you’re shooting in a huge house. For example, the spooky FOYER and the haunted LIBRARY. Or to point out a specific feature of a location.

You might also use a subheader to indicate a time leap. For example, you would put it under the subheader LATER if a cop is on a protracted stakeout and you want to show that time has passed.

This is one of the grey areas in the script format. Some (particularly those in production) argue that it should be slugged as a new scene (because of various time and possible setup requirements). On the other hand, writers prefer to save the line to avoid pushing the page. So, instead of saying INT. CAR – LATER, which takes up more room, they’d say LATER and carry on with the scene because the location never changed. Both methods are acceptable for script formatting, but utilizing subheaders is more informal.

Shots

Shots, which are formatted in the same way as a caps-locked action line, draw our attention to a certain image or way of experiencing things. This can contain a variety of camera shots, angles, and movements.

They are commonly employed by writer-directors nowadays. Still, they’re also used when the writer believes a visual is crucial to the entire scene and wants to make sure the director is aware of it.

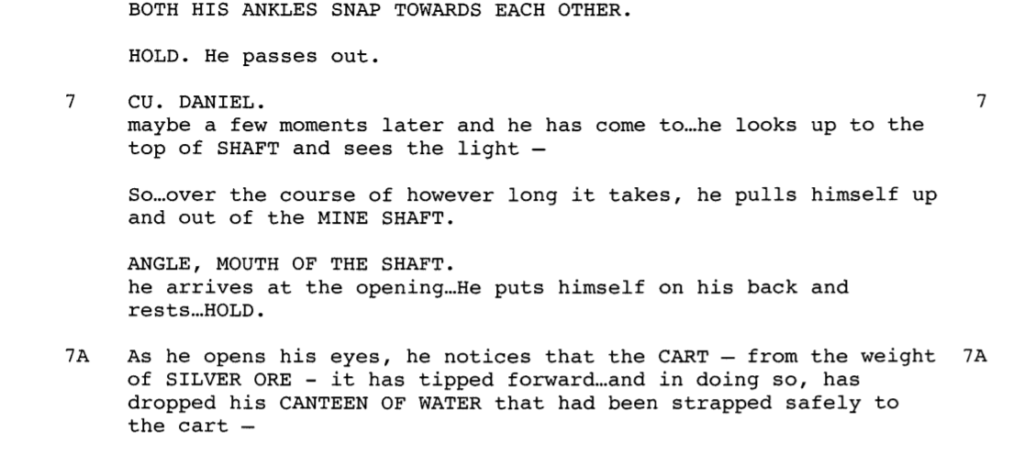

Here is an example of a screenplay from There Will Be Blood. P.T. Anderson (who also directed the film) uses different shots and angles throughout the script. It is preferable to leave these decisions out of your script unless you are directing the movie. For example, in this script, “Angle, Mouth of the Shaft” is given to instruct the cinematographer to place the camera accordingly.

Today, most screenwriters only mention shots when they are necessary for the scene’s interpretation. Keep in mind that by identifying different shot types in a script, you’re also emphasizing to the reader that this is a movie and that cameras will be filming it. Although, however, this can take the reader out of the plot on certain levels. You might want to utilize it sparingly.

Montage

Write “Begin Montage” as though it were a subheader to begin a montage, training or otherwise. Then, as you typically would, make a list of your scenes. Finally, close your montage with “End Montage,” written as if it were a subheader, once the montage is finished and Rocky has finally run up all those steps.

Here’s an example of a montage:

When writing a montage, there is certain leeway. For example, writers frequently list individual lines or lines separated by hyphens within the action to denote different montage locations and sub-scenes.

You will need a slugline for every shot or scene within a montage if you wish to arrange your script for production. That is because each location requires a unique setup and a unique set of production considerations.

Lyrics

When it comes to formatting a screenplay, lyrics can be problematic, especially when linked to the on-screen action. There is no “lyrics” aspect in any screenwriting software.

When studying how to create a screenplay, keep in mind that one page of a screenplay equals around one minute of screen time when done well. The word “approximately” should be emphasized. As lyrics take up a lot of page space but do not take as long to sing like music, you can throw off balance.

There are two ways to solve this issue:

- Space it Out: The lyrics can be stretched over the page, along with photos and movement directions. This will allow you to create some choreography as well as assist you set the rhythm and timing of your main musical act.

- Delineate the Sequence: Describe the overall feel of the music and the sequence that goes with it rather than listing each phrase. Damien Chazelle wrote the musical sections in his script for La La Land in this manner.

Leaving the actual lyrics out of the script saves space, but remember to account for the scheduling afterward. The “musical number” described above could take much longer to film than this brief reference implies.

Chyrons

Chyron is the writing displayed over the screen. It’s frequently used to tell the viewer what time and where the scene is taking place. This is something you’ll see a lot in military or spy movies.

Begin an action line with the word “CHYRON” (yep, in all caps), then the chyron’s text. Instead of “CHYRON,” some writers prefer to use “TITLE.” It’s a matter of personal preference. If you were to use Title, it would seem as follows:

In the movie’s screenplay, “Wrestler”, we can see the use of the term – CHYRON

Aside from the scene heading, here is another chance to describe the story’s environment or provide further information or context for the reader. The only difference would be that the word “Chyron” would be replaced with “Title.” Either one is acceptable as a script format.

End of Act

If you’re writing for network television, you’ll need to use a unique type of formatting. Put “End of Act One,” centered and underlined, into your script whenever you reach the end of an act. Then you skip a page and center and highlight “Act One” (or Act Two or Three) at the very top. If you’re using screenwriting software, opening your template as a “one-hour” or “half-hour” drama is critical. The screenwriting software may not include that part if you open it as a feature film script. Also, keep in mind that the script format for a single-cam sitcom versus a multi-cam sitcom is vastly different.

In essence, the single-cam is a movie script with act breaks. So while the multi-cam has double-spaced dialogue and capitalized action lines, the new acts begin halfway down the page. Each new scene starts on a new page. The single-cam has double-spaced dialogue and capitalized action lines (as we mentioned).

Make sure you know which one you’re working on before beginning to write. The tones, aesthetics, and productions of these two genres of comedies are vastly different. Therefore, it is vital that the reader understands which one you wrote, especially the production crew.

Physical Format of a Screenplay

Screenplays in the United States are printed single-sided on three-hole-punched paper in the usual letter size (8.5 x 11 inches). The top and bottom holes are then fastened together with two brass brads. The middle hole is left blank because it would make it more challenging to read the script rapidly if it were filled.

Double-hole-punched A4 paper is commonly used in the United Kingdom, slightly taller and narrower than US letter size. However, because the pages would be cropped if printed on US paper, some UK writers structure their screenplays for US letter size, especially when American producers read their scripts.

However, each country’s standard paper size is difficult to find in the other. As a result, British authors frequently provide an electronic copy to American manufacturers or crop the A4 to US letter size.

You can use a single brand at the top left-hand side of the page to bind a British script, making it quicker to flick through during script discussions. Screenplays are typically wrapped with a light cardboard cover and back page, with the logo of the production company or agency submitting the script prominently displayed. Covers are used to protect the script during handling, which might weaken the paper. Reading copies of screenplays are increasingly being supplied on both sides of the paper to reduce paper waste. They are occasionally shrunk to half their original size to create a compact book that may be read or carried in a pocket. This is usually done for the director or production staff to utilize while shooting.

Scripts are frequently provided by email, although most writing contracts still require the physical delivery of three or more copies of a finished script. Electronic documents facilitate copyright registration and provide evidence of “authorship on a specific date.” Authors can use the WGA‘s Registry to register their works and the FRAPA for television forms.

Screenplays for Documentaries

The screenplay format for documentaries and audio-visual presentations, which primarily consists of voice-over synchronized with still or moving images, is a two-column format that can be particularly challenging to create with typical word processors, at least when editing or rewriting. Templates for documentary formats are included in several script-editing software applications.

Screenwriting Software

Screenwriters can use a variety of screenwriting software products to assist them in following tight formatting guidelines. Screenplays, teleplays, and stage plays are all formatted using detailed computer tools. BPC-Screenplay, Celtx, Fade In, Final Draft, FiveSprockets, Montage, Movie Magic Screenwriter, Movie Outline 3.0, Scrivener, Movie Draft SE, and Zhura are some of the programs available. For example, Fade In Mobile and Scripts Pro are web applications that you can use from any computer and mobile device.

Script Coverage

Script coverage is a filmmaking phrase for the study and grading of scripts, which is usually done in a production company’s script development department. While coverage can be wholly verbal, it usually takes the form of a written report, which is guided by a rubric that varies by company. The initial concept behind coverage was that a producer’s assistant could read a script and then offer their boss an analysis of the project, recommending whether or not they should consider producing it.

Learning and Honing the Craft

Reading genuine scripts is the best method to learn how to write screenplays. It’s pretty easy to find screenplays for all of your favorite movies, thanks to the Internet. The formatting guidelines become evident after only a few pages of reading a script. By seeking out exceptional screenplays, you may discover tips and methods from Hollywood’s most successful writers. Once you’ve gotten used to writing scripts, you might find yourself wanting to be more adventurous with your writing. Also, you wish to break some of the conventions to give the reader a different experience.

Conclusion

The screenplay serves as a roadmap for the producers, directors, actors, and crew regarding what will be seen on the big screen. It is the common ground on which everyone working on the film will collaborate from start to end. It tells the entire story and includes all of the film’s actions and conversations with each character. It can also be used to visually characterize characters so that filmmakers can strive to recreate their style, appearance, or feel. Finally, the script is the best predictor of cost because it is the movie or TV show template. Making a film necessitates meticulous budget preparation, and the easiest way to estimate costs is to look at the script.